To print this article, all you need is to be registered or login on Mondaq.com.

1 Legal framework

1.1 Which legislative and regulatory provisions govern corporate immigration in your jurisdiction?

Legislation: The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) and other public laws govern immigration in the United States. The INA, passed by Congress and signed by the president in 1952, consolidated many existing provisions and reorganised the structure of immigration law. It has been amended many times over the years based on new public laws enacted by Congress. With every new law affecting immigration, Congress either amends the INA or passes the law without amending the INA.

Regulations: The INA and most other immigration laws are codified in Title 8 (Immigration and Nationality) of the United States Code (or Code of Federal Regulations (CFR)). The most frequently used US Code sections for corporate immigration lawyers are:

- Title 8 (Immigration and Nationality);

- Title 20 (Employees’ Benefits);

- Title 29 (Labor); and

- Title 22 (Foreign Relations);

Other US Code sections relevant to practitioners include:

- Title 6 (Domestic Security);

- Title 18 (Crimes and Criminal Procedure);

- Title 19 (Customs Duties);

- Title 28 Judicial Administration;

- Title 42 (Public Health); and

- Title 45 (Public Welfare).

1.2 Do any special regimes apply in specific sectors?

N/A.

1.3 Which government entities regulate immigration in your jurisdiction? What powers do they have?

The US president can impact immigration on grounds of national health and/or security. For example, various COVID-19-based executive orders limited the entry of both immigrants and non-immigrants whose work visas were sponsored by US companies (see Proclamations 10014 and 10052).

The US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was created under the administration of George W Bush in November 2002 in response to the terrorist attacks of 9/11. With the primary mission to protect the United States, the DHS unified 22 different federal departments and agencies into one cabinet agency. Of the many offices and agencies that now make up the DHS, there are three federal agencies that directly regulate immigration:

- US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) manages the US immigration system and determines or grants immigration benefits;

- US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) handles immigration at the border, ensuring lawful entry into the United States; and

- US Immigration and Customs Enforcement enforces immigration laws within the United States.

The United States, through its consulates and embassies around the world, administers the issuance of both non-immigrant and immigrant visas.

The United States has jurisdiction over the labour certification process – a mandatory component of certain employment-based visa applications such as the H-1B, E-3 and Program Electronic Review Management-based green card sponsorship.

The Executive Office for Immigration Review administers and interprets federal immigration law and regulations through immigration court proceedings, appellate reviews and administrative hearings.

1.4 What is the government’s general approach to immigration in your jurisdiction?

US immigration policies and adjudication trends tend to be dictated by the political and economic climate. Although the INA and the US Code provide the legal framework, the rules and regulations are written such that federal agencies/officers have significant discretionary authority over the interpretation and application of those rules. In turn, corporate immigration lawyers must always keep abreast of the various immigration agencies’ policies and adjudication trends in addition to the nation’s political and economic climate when approaching every case. See also question 9.

2 Business travel

2.1 Do business visitors need a visa to visit your jurisdiction? What restrictions and exemptions apply in this regard?

Business visitors must apply for a B-1 Business Visitor visa when participating in certain business or commercial activities in the United States. Certain exceptions apply, as discussed below.

Visa Waiver Program or Visa Waiver for Business: Business visitors who are citizens or nationals of participating Visa Waiver Program (VWP) countries may enter the United States without obtaining a visa if the following requirements are met:

- The duration of the visit is for no more than 90 days;

- The purpose of the visit is a legitimate business activity in line with the B-1 Business Visitor visa (see questions 2.2 and 2.4);

-

The business visitor is a citizen or national of one of the participating VWP countries (the list of VWP countries is subject to change and is available here); -

The business visitor possesses a valid Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA) approval at the time of entry. ESTA is a web-based system administered by CBP to determine eligibility to travel under the VWP; and -

The business visitor possesses a valid passport that is embedded with an electronic chip (known as an ‘e-passport’), which must be valid for at least six months from the intended US departure date (for further details please see the VWP requirements).

Canadian citizens: In general, Canadian citizens are US visa exempt; they are not required to secure a US visa stamp in order to enter the United States. Instead, Canadians are granted admission under the applicable visa type at the US port of entry or land border. However, Canadian-citizen business visitors should nonetheless be prepared to present documentation demonstrating that the purpose of their US visit is aligned with B-1 business activities and meets the B-1 requirements (see questions 2.2 to 2.4).

2.2 Do the requirements vary depending on sector or purpose?

To be eligible to enter the United States, business visitors applying for a B-1 Business Visitor visa or seeking admission under the VWP should be prepared to demonstrate that the following requirements are met:

- The purpose of the trip to the United States is for business of a legitimate nature (see question 2.4);

- The business activity/visit is for a specific limited period;

- The business visitor has sufficient funds to cover the expenses of the trip and his or her stay in the United States (typically covered by either the visitor or his or her employer). It is possible for a hosting US entity to cover expenses (travel, lodging, meals) as long as payment is not in exchange for employment. An honorarium is also acceptable in limited circumstances, such as for a conference guest lecturer;

- The business visitor maintains residence and employment outside the United States, neither of which the visitor has any intention of abandoning, as well as other binding ties that will ensure his or her return abroad at the end of the visit; and

- The business visitor is otherwise admissible to the United States.

2.3 What is the maximum stay allowed for business visitors?

B-1 Business Visitor visa:

- Initial period of stay (one to six months): At the US port of entry, CBP will grant the business visitor an initial period of stay sufficient for him or her to complete his or her business activities, not to exceed a period of six months.

-

Extension of stay (up to six months; the total maximum period of stay for a given business trip is one year): If a business visitor needs to extend his or her stay beyond the period initially granted at the port of entry, the visitor may extend his or her stay for a maximum of six months by filing Form I-539, Application to Extend/Change Nonimmigrant Status, in which he or she must demonstrate that he or she continues to meet all B-1 requirements outlined in questions 2.2 and 2.4.

Visa Waiver for Business: Business visitors entering on the Visa Waiver for Business will be granted a period of stay for no more than 90 days. The visitor must depart the United States by no later than the expiration date granted at the time of entry. Extensions of stay are not available.

2.4 What activities are business visitors allowed to conduct while visiting your jurisdiction?

Business visitors are permitted to participate in business activities of a commercial or professional nature in the United States, including, but not limited to:

- consulting with business associates;

- attending business meetings that do not involve gainful employment;

- attending a scientific, educational, professional or business convention, or conference as an attendee or guest speaker/lecturer on specific dates;

- settling an estate;

- negotiating a contract;

- participating in short-term training that does not involve gainful employment; or

- transiting through the United States (certain persons may transit the United States with a B-1 visa).

(See 9 Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM)41.31.)

2.5 Is authorisation required for business visitors to provide or receive short-term training?

Participation in short-term training is a permissible business activity and does not require a special or separate authorisation. However:

- the training programme should not involve gainful employment; and

- the business visitor should not receive any income or payment from the US entity, except for an expense allowance/reimbursement for lodging, meals and/or transportation.

The business visitor seeking entry for the purposes of short-term training should be prepared to present documentation demonstrating the following:

- The training will benefit his or her employer/employment abroad;

- He or she maintains a residence and employment abroad;

- He or she continues to receive an income from the employer abroad and not the US entity hosting the training programme; and

- The duration of the training is definitive and short term.

The extent of this evidence will depend on the intended period of stay or the duration of the programme. Depending on the circumstances surrounding the short-term training programme, a H-3 Trainee visa or J-1 Trainee visa may be more suitable.

3 Work permits

3.1 What are the main types of work permit in your jurisdiction? What restrictions and exemptions apply in this regard?

The US immigration system provides for a wide variety of work-authorised visa classifications. Some of the most common work visas include the following:

|

Visa type |

Purpose |

|

E-1 |

Treaty traders |

|

E-2 |

Treaty investors |

|

E-3 |

Specialty occupation workers from Australia |

|

H-1B |

Specialty occupation workers |

|

H-1B1 |

Specialty occupation workers from Chile/Singapore |

|

H-2A |

Seasonal agricultural workers |

|

H-2B |

Seasonal non-agricultural workers |

|

L-1A |

Intracompany transferees employed in an executive/managerial role |

|

L-1B |

Intracompany transferees employed in a specialised knowledge capacity |

|

O-1 |

Individuals with extraordinary ability or achievement |

|

P |

Athletes and members of entertainment groups |

|

TN |

Canadian and Mexican professionals, as defined by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) |

3.2 What is the maximum stay allowed under each type of work permit? Can this be extended?

|

Visa type |

Maximum stay and extensions* |

|

E-1 Treaty Traders |

|

|

E-2 Treaty Investors |

|

|

E-3 Australian Professionals |

|

|

H-1B Professionals |

|

|

H-1B1 Chile/Singapore Professionals |

|

|

H-2A Seasonal Agricultural Workers |

|

|

H-2B Seasonal non-Agricultural Workers |

|

|

L-1A Intracompany Transferees, Managers/Executives |

|

|

L-1B Intracompany Transferees, Specialized Knowledge |

|

|

O-1 Extraordinary Ability |

|

|

P-1/2/3 Athletes/Artists/Entertainers |

|

|

TN Canadian/Mexican Professionals |

|

*The adjudicating officer always has the discretionary authority to shorten the requested period of stay for any visa type.

3.3 What criteria must be satisfied to obtain each kind of permit?

|

Visa type |

Visa criteria – petitioner must document the following: |

|

E-1 Treaty Traders |

|

|

E-2 Treaty Investors |

|

|

E-3 Australian Professionals |

|

|

H-1B Professionals |

|

|

H-1B1 Chile/Singapore Professionals |

|

|

H-2A Seasonal Agricultural Workers |

|

|

H-2B Seasonal Non-Agricultural Workers |

|

|

L-1A Intracompany Transferees, Managers/Executives |

|

|

L-1B Intracompany Transferees, Specialized Knowledge |

|

|

O-1 Extraordinary Ability |

|

|

P-1/2/3 Athletes/Artists/Entertainers |

|

|

TN Canadian/Mexican Professionals |

|

3.4 Do any language requirements apply for each kind of permit?

No. In general, the US immigration system does not require any particular language skills, unless specified by the sponsoring/petitioning employer.

3.5 Are any work permits subject to quotas?

Several work visa classifications are subject to annual quotas. For instance, the H-1B category is subject to an annual numeric cap of 65,000 plus an additional 20,000 slots for individuals holding a master’s degree from a US college or university. Non-profit employers seeking H-1B status are not subject to the annual cap. In addition, previous beneficiaries of cap-subject H-1B petitions are not subject to the quota.

Similarly, the H-2B visa category is limited to a quota of 22,000 per year. H-1B1 visas for Chilean and Singaporean nationals are subject to an annual cap of 1,400.

3.6 Do any specific rules apply with regard to the following:

(a) Work in specific sectors?

(b) Shortage occupations?

(c) Highly skilled workers?

(d) Investors and high-net worth individuals?

(a) Work in specific sectors?

Several US work visa categories are sector specific. For instance, H-2A visas are intended for temporary agricultural workers, while H-2B visas are designated for seasonal workers in non-agricultural sectors. P visas are designated for internationally recognised athletes, entertainers and artists.

(b) Shortage occupations?

Most non-immigrant visa categories do not require the petitioner to establish a labour shortage for the occupation in question. However, petitioners seeking H-2A or H-2B visas must establish that there are not enough US workers who are able, willing, qualified and available to do the temporary work.

(c) Highly skilled workers?

Highly skilled workers most often seek the H-1B, H-1B1, E-3, L-1A, L-1B, O-1 or TN visa classifications; although the H-1B1, E-3 and TN visa classifications are reserved specifically for professionals/highly skilled workers of a particular nationality (H-1B1: Chilean/Singaporean; E-3: Australian; and TN: Canadian/Mexican). Researchers, scientists, artists, business executives and professionals who at are the very top of their field and can meet the government’s regulatory requirements will typically seek the O-1 Extraordinary Ability visa classification.

(d) Investors and high-net-worth individuals?

The E-1 visa category is available to owners of enterprises that engage in substantial trade between the United States and a country with which the United States maintains a treaty of commerce and navigation.

Similarly, the E-2 visa is available to investors from commerce/navigation treaty countries. E-2 investor applicants must:

- have invested, or be actively in the process of investing, a substantial amount of capital in a bona fide enterprise in the United States; and

- show that the investment is irrevocably committed, a real and operating enterprise, and not marginal or ‘at risk’ in a commercial sense.

3.7 What are the formal and documentary requirements for obtaining each kind of permit?

In general, the regulatory agencies charged with administering US immigration law require those seeking immigration benefits to present documentary evidence that the petitioner/applicant has satisfied each of the regulatory requirements for a given visa classification. Question 3.3 outlines the criteria that must be documented for each type of work visa.

3.8 What fees are payable to obtain each kind of permit?

A list of current fees for each work visa is set out below (see US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Fees and Consular Processing Fees for up-to-date information in this regard).

|

Visa type |

Fees |

|

E-1 |

|

|

E-2 |

|

|

E-3 |

|

|

H-1B |

|

|

H-1B1 |

|

|

H-2A |

|

|

H-2B |

|

|

L-1A |

|

|

L-1B |

|

|

O-1 |

|

|

P |

|

|

TN |

|

3.9 What is the process for obtaining a permit? How long does this typically take?

Applying from abroad: Applicants for certain visa types (E-1, E-2, E-3, H-1B1 and TN) may apply for the work visa directly at a US consulate in their local jurisdiction. However, for those seeking the H-1B, H-2A, H-2B, O-1 or P visa classifications, the petitioning US employer must first secure an approval from USCIS by submitting a Form I-129 petition. Once the visa classification has been approved by USCIS, the prospective employee may then apply for the visa stamp at a US consulate in his or her local jurisdiction.

Applying while in the United States: In certain cases, where a prospective employee is already lawfully studying/working and living in the United States, it is possible that he or she may not need to depart the United States and may instead be eligible to change or transfer his or her immigration status to the visa classification sponsored by the petitioning US employer. In such cases, the US employer need only file the visa petition with USCIS.

Work visas requiring a certified LCA: As indicated in question 3.3., several visa classifications require LCAs to be filed with and certified by the DOL prior to submitting the visa petition to USCIS or the US consulate. The H-1B, H-1B1 and E-3 classifications, for instance, require an LCA to be filed with and certified by the DOL. For the H-2A and H-2B classifications, petitioners must first obtain a temporary labour certification from the DOL and then submit this certification as part of the petition filed with USCIS.

Individual L-1 versus Blanket L-1: For the L-1A and L-1B visa categories, a USCIS petition is required unless the petitioner has existing Blanket L-1 approval. Qualified L-1 visa applicants may apply directly at the US consulate if their employer has existing Blanket L-1 approval (see question 6.6).

Timeline: The timeline for obtaining a work-authorised visa varies widely depending on the visa classification sought, as well as on visa appointment waiting times at the local US consulate and Department of State processing times. Generally, classifications that require a petition approval take longer and the exact timeframes vary depending on the agency’s workload. However, petitioners seeking USCIS approval can request a Premium Processing service for a fee of $2,500. The Premium Processing service guarantees that USCIS will act on the petition within 15 calendar days.

Canadians: Canadians do not require a visa stamp issued by a US consulate and instead may apply for visa classification and admission directly at a US port of entry.

3.10 Once a work permit has been obtained, what are the rights and obligations of the permit holder? What are the penalties in case of breach?

Once a work visa/permit has been obtained, the permit holder must maintain his or her visa status by ensuring that his or her work activities are aligned with the information as presented to, and approved by, the US government. Further, each of the work permits discussed in question 3 is employer specific and the permit holder must thus remain employed by the petitioning employer for the entire duration of his or her stay. If the permit holder wishes to terminate his or her employment and work for another US employer, that employer must formally ‘transfer’ the holder’s work visa/permit and assume sponsorship of the respective employee’s work visa by filing a petition with the government.

Likewise, the sponsoring employer must ensure that work activities and conditions remain aligned with the information as presented to, and approved by, the US government. For certain visa types (eg, H-1B, H-1B1 and E-3), the employer must maintain certain minimum salary requirements; work location or job changes may necessitate an amendment. Further, if the employer terminates a H-1B employee prior to the work permit’s expiration date, it must pay for the H-1B employee’s return transportation home. Non-compliance can result in serious monetary and legal sanctions for the employer.

4 Settlement

4.1 What are the criteria for obtaining settlement in your jurisdiction? What restrictions apply in this regard?

There are two major pathways to secure ‘settlement’, or US permanent residency:

- family-based sponsorship; and

- employment-based sponsorship.

Family-based sponsorship: Under this pathway, permanent residency is secured through the sponsorship of a US family member who is either a US citizen or a US permanent resident. Eligibility to apply for permanent residency depends on the familial relationship, marital status and age of the foreign national:

- US citizen sponsorship: US citizens who are at least 21 years of age may sponsor their spouse, children (irrespective of age and marital status), siblings and parents.

- US permanent resident sponsorship: US permanent residents who are at least 21 years of age may sponsor their spouse and unmarried children.

Under the family-based pathway, there are a total of four preference categories:

- First preference (F1): Unmarried sons and daughters (21 years of age and older) of US citizens;

- Second preference (F2A): Spouses and children (unmarried and under 21 years of age) of lawful permanent residents;

- Second preference (F2B): Unmarried sons and daughters (21 years of age and older) of lawful permanent residents;

- Third preference (F3): Married sons and daughters of US citizens; and

- Fourth preference (F4): Brothers and sisters of US citizens (if the US citizen is at least 21 years of age).

The family-based pathway also includes ‘immediate relatives’, defined as:

- spouses of US citizens;

- unmarried children under 21 years of age of a US citizen parent; or

- parents of a US citizen child who is at least 21 years of age.

Employment-based sponsorship: Under this pathway, permanent residency is secured based on employment in the United States. There are a total of five employment-based preferences; of these, the first three preference categories are the most commonly pursued, requiring the sponsorship of a US employer whose intent is to offer the individual long-term employment upon obtaining US permanent residence status. Within each preference, there are categories as follows:

-

First Preference EB-1 (‘priority workers’): -

- individuals with ‘extraordinary ability’ in the sciences, arts, business, education or athletics;

- ‘outstanding professors’ or ‘outstanding researchers’; and

- multinational (or intracompany) managers and executives.

-

Second Preference EB-2: -

- individuals in professions holding an advanced degree or its equivalent;

- individuals of ‘exceptional ability’ in the sciences, arts or business; or

- individuals whose employment is in an area of a national interest and whose ability in that area of national interest is ‘exceptional’.

-

Third Preference EB-3: -

- ‘professionals’ whose US job offer is of a profession that requires a minimum of a US bachelor’s degree (or foreign equivalent) and who meet those minimum requirements;

- ‘skilled workers; whose US job offer requires a minimum of two years’ experience or training; and

- ‘unskilled workers’ whose US job offer is to perform unskilled labour requiring less than two years’ training, education or experience.

-

Fourth Preference EB-4 (‘special immigrants’): -

- ‘religious workers’ – that is, ministers and non-ministers in religious vocations or occupations, where the purpose of their long-term stay in the United States is to perform religious work in a full-time compensated position. (The non-minister religious worker programme sunsetted on 18 February 2022);

-

‘special immigrant juveniles’ – that is, unmarried children under 21 years of age who are under juvenile court protection because of abuse, abandonment or neglect by a parent and are unable to return to their home country or last country of residence (8 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) § 204.11; US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Policy Manual, Volume 6, Part J- Special Immigrant Juveniles); - broadcasters for the United States Agency for Global Media; and

- other special immigrants, including retired officers/employees of G-4 international organisations or NATO-6, employees of the US government who are abroad and certain licensed and practising physicians.

- Fifth Preference EB-5 (‘immigrant investors’) – investors who generate employment in the United States. This was established by Congress in 1990 to stimulate the economy by creating jobs through foreign investment in new commercial enterprises in the United States. The programme has been reauthorised or extended by Congress and the president over the years. On March 12, 2022, Congress enacted new legislation re-authorising the EB-5 Immigrant Investor Regional Center Program.

4.2 Do any specific rules apply to foreign citizens with ancestral connections?

Only very limited rules.

Foreign nationals with the following US ancestral connection(s) may qualify for US permanent residency:

- a married or unmarried child (no age limit) of a US citizen;

- an unmarried child (no age limit) of a US permanent resident;

- a parent of a US citizen (the US citizen child must be at least 21 years of age to sponsor his or her parent); or

- a widow or widower of a US citizen

Immediate relatives: Permanent residency is “immediately available” to those foreign nationals who are ‘immediate relatives’. In other words, unlike other permanent residency categories, there are no numerical visa limitations for immediate relatives and therefore a green card visa is immediately available to immediate relatives. Those who qualify simply need to submit their Form I-130 and I-485 applications to the government and need not wait for a visa to become available (see question 4.5).

A foreign national is an ‘immediate relative’ if he or she is:

- the spouse of a US citizen;

- an unmarried child under 21 years of age of a US citizen; or

- the parent of a US citizen child who is at least 21 years of age.

4.3 What are the formal and documentary requirements for obtaining settlement?

The formal and documentary requirements for obtaining US permanent residency under the three employment-based preferences mentioned in question 4.1 are as follows.

EB-1:

|

Categories |

Overarching requirement |

Documentary evidence |

Offer of long-term employment required? |

|

Individuals with ‘extraordinary ability’ in the sciences, arts, business, education or athletics (8 CFR §204.5(h)). |

The individual can demonstrate extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business or athletics through sustained national or international acclaim. |

To be eligible, the individual must submit adequate documentation evidencing that he or she has sustained national or international acclaim and that his or her achievements have been recognised in the field of expertise. In making its decision, USCIS considers the following types of evidence:

The successful applicant need not meet all of the regulatory criteria outlined above. Rather, a minimum of three must be met, such that the overall evidence demonstrates that “the individual is one of a small percentage who have risen to the very top of the field of endeavor”.

|

No. Individuals under this category have the option of petitioning their own US permanent residency or applying for permanent residency through the sponsorship of a US employer. |

|

Outstanding professors or outstanding researchers (8 CFR §204.5(i)) |

|

|

The job offer must be for tenure/tenure-track teaching or a comparable research position at a university, institution of higher education or private employer. |

|

Multinational (or intracompany) managers and executives (8 CFR §204.5(j)) |

|

‘Managerial capacity’ is defined an assignment within an organisation in which the employee:

‘Executive capacity’ means an assignment within an organisation in which the employee:

(Section 101(a)(44) of INA and 8 CFR 204.5(j)(2))

|

Yes; see documentary evidence for letter details. |

EB-2:

|

Categories |

Overarching requirement |

Documentary evidence |

Sponsoring employer’s responsibilities |

|

Advanced degree: For individuals of professions holding an advanced degree or its equivalent (8 CFR 204.5(k)(2)) |

|

|

|

|

Exceptional ability: Individuals of ‘exceptional ability’ in the sciences, arts or business (8 CFR 204.5(k)(2)-(4); 20 CFR 656.15(d)(1)) |

|

The individual must meet the ‘exceptional ability’ requirements under both DOL and USCIS regulations.

DOL requirements: The petitioning employer must submit the following on behalf of the beneficiary-employee:

USCIS requirement: The petitioning employer must submit documentation demonstrating that the benefiting employee meets at least three of the following criteria:

(8 CFR 204.5(k)(3)(ii)) |

However, the US employer must nonetheless:

|

|

National interest waiver: Individuals whose employment is in an area of national interest (8 CFR §204.5(k)(4)(ii)) |

US employer sponsorship is not required. Instead, those seeking a national interest waiver may self-petition and may file their labour certification directly with USCIS along with their Form I-140, Petition for Alien Worker.

Though no statutory authority exists, USCIS will typically grant national interest waivers to those who meet the exceptional ability requirements (see above) and whose employment in the United States would greatly benefit the nation (see Matter of Dhanasar, 26 I&N Dec 884 (AAO 2016)). |

|

Must demonstrate to USCIS its ability to pay the proffered waged as listed on the petition as of the Form I-140 filing date. |

EB-3:

|

Categories |

Overarching requirement |

Documentary evidence |

Sponsoring employer’s responsibilities |

|

Professionals (8 CFR 204.5(k)(3)) |

The individual must meet the minimum US bachelor’s degree requirement or its foreign equivalent and any other skill requirements contained in the PERM application filed by the sponsoring US employer and certified by the DOL. |

|

|

|

Skilled workers (8 CFR 204.5(k)(3)) |

The individual must meet the minimum two years of work experience, education or training and any other skill requirements contained in the PERM application filed by the sponsoring US employer and certified by the DOL. |

|

|

|

EB-3 unskilled workers (8 CFR 204.5(k)(3)) |

The individual must demonstrate the ability to perform the unskilled labour (requiring less than two years of training or experience) and any other skill requirements contained in the PERM application filed by the sponsoring US employer and certified by the DOL. |

|

|

4.4 What fees are payable to obtain settlement?

The table below sets out the US government filing fees pertaining to employment-based green card processes described in question 4.3:

|

Name of application/form |

Government fee* |

|

Application for Permanent Labor Certification (PERM) |

None |

|

Form I-140, Immigrant Visa Petition |

$700 |

|

Form I-485, Adjustment of Status Application (Age 14-78) |

$1,225 |

|

Form I-485, Adjustment of Status Application (Under age 14 years, and filing with parent) |

$750 |

|

Form I-485, Adjustment of Status Application (Under age 14 and filing without parent) |

$1,140 |

|

Form I-485, Adjustment of Status Application (Age 79 or older) |

$1,140 |

|

Premium Processing (guarantees USCIS government adjudication in 15 calendar days. Currently available for only certain I-140 categories) |

$2,500 |

For a comprehensive list of fees pertaining to all green card pathways, including Form I-130, family-based sponsorship and consular processing, please visit USCIS Fees and Consular Processing Fees.

4.5 What is the process for obtaining settlement? How long does this typically take?

Obtaining settlement or US permanent residency entails either a two or three-stage green card application process, depending on the immigrant visa preference category that serves as the underlying basis for the green card application.

|

Immigrant visa preference category |

Green card application process |

|

All EB-1 categories |

Two-stage application process:

|

|

EB-2: Exceptional Ability |

|

|

EB-2: National Interest Waiver |

|

|

All family-based preference categories |

|

|

EB-2: Advanced Degree or Equivalent |

Three-stage application process:

|

|

All EB-3 categories |

PERM labour certification: For certain employment-based EB-2 and EB-3 immigrant visa preference categories (see question 4.3), a prerequisite to filing the Form I-140 Immigrant Visa Petition is securing a certified PERM from the DOL. In such cases, it is the sponsoring US employer that must file for both the PERM and the I-140 on behalf of the beneficiary employee or prospective employee. The US employer must meet certain employer obligations, including:

- a good-faith test of the US labour market for a US worker who is willing, able, available and qualified for the sponsored job opportunity (and confirmation that no such US worker was identified or available);

- the intent to offer the individual a long-term position as described in the application by the time the individual is granted permanent residency; and

- the financial ability to pay the proffered salary among other employer obligations throughout the sponsorship process.

(See 20 CFR 655 and 8 CFR 204.5.)

Immigrant visa petition: Applying for US permanent residency is a multi-stage application process. Whether applying for permanent residency from abroad or in the United States, the individual must secure an approved immigrant visa petition. For employment sponsorship, this visa petition is known as the Form I-140 Immigrant Visa Petition; whereas for family sponsorship permanent residency applicants, the immigrant visa petition is known as the Form I-130 Immigrant Visa Petition. The immigrant visa petition under both the employment and family-based routes contains several preference categories. An individual’s eligibility for a green card is based on one of those preference categories. The approved immigrant visa preference category then forms the basis for the green card application and will determine how quickly the individual receives his or her green card.

Individual background application (‘Form I-485 Adjustment of Status’ or ‘consular processing’): Aside from securing government approval of the relevant immigration visa, applicants must also undergo an application process that evaluates their background, to include aspects such as:

- work and residence history;

- family and marital status;

- arrest record/criminal history;

- membership of military/political organisations;

- US immigration history; and

- medical/vaccination report.

For applicants applying in the United States, this application stage is known as Form I-485 or I-485 Adjustment of Status Application (AOS). Once the AOS is approved, the physical green card is produced and mailed to the US applicant, at which time he or she has officially secured permanent residency.

For applicants applying for a green card while abroad, this background application stage is known as ‘consular processing’: the individual must go to the US consulate for an interview and his or her background documents will be submitted to the National Visa Center prior to the interview. If approved, the US consulate will issue an immigrant visa stamp in the individual’s passport and the individual can then enter the United States based on the immigrant visa. Upon entry into the United States, US Customs and Border Patrol will then admit the individual as a US permanent resident. Once admitted as a US permanent resident, the physical green card is mailed to the individual’s US residence.

Timeframe: Applying for a green card is a lengthy process that entails multiple steps. Aside from completion of the various requirements outlined above, green card applicants (and petitioning employers) should consider two factors that are beyond their control:

- government processing times; and

- visa availability

Government processing times: Each of the application stages above will require the adjudication of the respective government agency with jurisdiction over that particular application process. Government processing times vary and applicants should refer to the respective government agency websites for the most current government processing times.

Visa availability: Whether applying for the green card through the two-stage or three-stage process, the PERM application and the immigrant visa petition stages may be pursued as soon as the employer and employee have met all requirements and can produce the required documentation (see above). There are no quota limits in terms of the number of PERM applications which the government may approve; nor are there numerical limitations on the number of I-130 or I-140 Immigrant Visa Petitions approved. However, the government has set numerical limitations on the number of green card visas allotted per year. Therefore, irrespective of the two-stage or three-stage process, an individual cannot proceed with the last application stage (I-485 AOS or consular processing) until a green card visa is available.

The government and the regulations refer to the green card numerical limitation as a numerical limitation on ‘immigrant visas’. Its usage of the term ‘immigrant visa’ in this numerical limitation context should not be confused with its ability to grant the I-130 or I-140 Immigrant Visa Petition, as there are no numerical limitations on the number these granted per year. Therefore, for clarity, we use the term ‘green card visa’.

Whether a green card visa is available will depend on several variables:

- the applicant’s country of birth or chargeability;

- the applicant’s immigrant visa preference category;

- the applicant’s immigrant visa priority date; and

- supply and demand.

An individual’s immigrant visa priority date is the date on which the I-130 or I-140 Immigrant Visa Petition is filed and is reflected on the government’s immigrant visa receipt or approval notice. However, for certain employment preference categories where a PERM labour certification is a prerequisite to filing the I-140 petition, the date on which the PERM was filed is the priority date and is subsequently reflected on the government’s I-140 receipt or approval notice.

Each month, the DOS releases a Visa Bulletin identifying the priority dates that are ‘current’ or ripe for the last application stage submission and approval – based on country of birth and preference category. USCIS will then use the DOS Visa Bulletin to determine which I-485 AOS applications it will accept and adjudicate for that particular month (in-county applicants); and US consulates and embassies will similarly use the DOS Visa Bulletin to determine which consular processing applicants will be afforded an interview (abroad applicants). Unlike the I-485 application, where the in-country applicant must closely monitor both the monthly DOS Visa Bulletin and the USCIS website to discern when his or her priority date is ripe for application submission, consular processing applicants applying from abroad should automatically receive an interview notification from the US consulate or embassy within several weeks of their priority date becoming current. Therefore, the applicant’s priority date, preference category and country of birth/chargeability determine his or her ‘place in line’ for the green card.

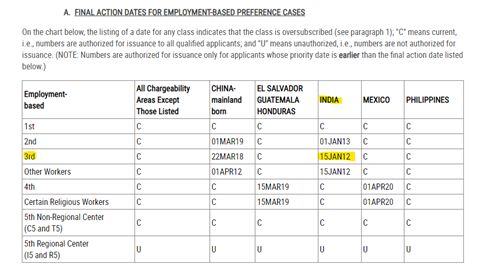

Numerical limitations: Only 226,000 family-based visas and 140,000 employment-based visas are allotted annually. If any visas are unused in a given fiscal year, the visa numbers roll over to the following year. However, for many of the family-based preference categories, as well as for EB-2 and EB-3 India or mainland China-born applicants, demand exceeds supply. For example, based on the below February 2022 Visa Bulletin, the government is only issuing green cards to EB-3 India-born applicants with a priority date earlier than 15 January 2012. This means that a typical India-born applicant filing for a green card under the EB-3 preference category must currently wait 10 to 12 years before receiving his or her green card (this estimate takes into account current USCIS processing times of up to 18 months).

(See US Department of State February 2022 Visa Bulletin.)

Exceptions to numerical limitations – ‘immediate relatives’: As mentioned in question 4.2, US permanent residency is “immediately available” to those foreign nationals who are ‘immediate relatives’. In other words, unlike all other immigrant visa preference categories, there are no numerical visa limitations for immediate relatives and therefore a green card ‘visa’ is immediately available to immediate relatives. Those who qualify simply need to submit their Form I-130 and I-485 applications to the government and need not wait for a visa to become available, but should still account for government processing times.

A foreign national is an immediate relative if he or she is:

- the spouse of a US citizen;

- an unmarried child under 21 years of age of a US citizen; or

- the parent of a US citizen child who is at least 21 years of age.

Employment-based categories that typically exceed supply: The EB-1 preference category (‘priority workers’) typically remains current year-round, irrespective of birth/chargeability country. In the occasional months where the EB-1 category retrogresses (typically in the summer/autumn, when the fiscal year end is nearing), this category will typically become current again by October of the new fiscal year.

4.6 Is the settlement process the same for EU citizens?

Yes.

5 Dependants

5.1 What are the criteria to qualify as a dependant? What restrictions apply in this regard?

To qualify as a dependant, an individual must be the spouse or child of the principal applicant or beneficiary. To qualify as a child dependant, the child must be unmarried and under the age of 21. Dependent applicants must prove their relationship to the principal visa holder. For instance, spouse-dependent applicants must present a marriage certificate; while a child-dependent applicant must submit a birth certificate and/or adoption papers establishing the age of the child and the legal relationship between the child and the principal applicant.

5.2 What rights do dependants enjoy once admitted as such?

As of 31 January 2022, E and L spouse-dependants are automatically eligible to work upon lawful admission into the United States. They are no longer required to apply separately for a work permit; rather, mere admission as a E or L spouse-dependant automatically provides lawful work authorisation.

In addition, certain H-4 visa holders (dependants of H-1Bs) may apply to US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) for an employment authorisation document (EAD). Specifically, H-4 spouses may apply for an EAD if the principal H-1B holder has an approved I-140 Immigrant Visa Petition and has been granted H-1B status beyond his or her six-year maximum stay under the American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act

Dependants of other visa categories (eg, the J-1) and those with pending I-485 Adjustment of Status applications related to the green card process may also apply for an EAD/work permit.

5.3 How are civil/unmarried partners and same-sex partners treated in this regard?

Married same-sex partners are fully eligible for dependant visas. Civil/unmarried partners are generally not eligible for dependant visas, but may apply for B-2 Domestic Partner visas. However, B-2 domestic partners are only admitted to the United States in increments of six months, and then must either travel outside the United States or file an I-539 extension of status petition with USCIS.

6 Intra-company transfers

6.1 Is there a specific regime for the transfer of employees from an overseas branch of a multinational to your jurisdiction?

Yes. Under the L-1 Intracompany Transferee visa, a US employer may transfer employees from one of its overseas/foreign branch offices to one of its offices in the United States, provided that all visa requirements are met. By the same token, a foreign company that does not yet have an office in the United States but wishes to establish one may leverage this L-1 visa to send an executive, manager or specialised knowledge employee for the purpose of establishing one.

The L-1 Intracompany Transferee visa classification includes two subcategories:

- L-1A Intracompany Transferee Executive or Manager, intended for the transfer of managers or executives to the United States; and

- L-1B Intracompany Transferee Specialized Knowledge, intended for the transfer of employees with specialised knowledge specific to the company.

(See Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) §101(a)(15)(L); 8 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) §214.2(l).)

6.2 What is the maximum stay allowed under this regime? Can this be extended?

L-1 visas are typically issued for an initial validity period of three years. L-1A visas can be extended in two-year increments for a maximum stay of seven years. The L-1B classification can also be extended for a maximum stay of five years.

|

L-1 Visa sub-categories |

Initial period of authorised stay |

Maximum period of stay |

|

L-1A Managers & Executives |

Three years |

Seven years |

|

L-1B Specialized Knowledge |

Three years |

Five years |

6.3 What criteria must the employer satisfy to obtain a permit under this regime?

For both the L-1A and L-1B classifications, the US petitioning employer must satisfy the following initial requirements:

- Qualifying relationship: The employer must have a qualifying relationship with a foreign company that is a parent, branch, subsidiary or affiliate.

- Doing business: The employer must currently or will be doing business in the United States and in at least one other country directly or through a qualifying organisation for the duration of the beneficiary’s stay in the United States as an L-1. ‘Doing business’ means that the employer is engaged in “regular, systematic and continuous provision of goods and/or services by a qualifying organization and does not include the mere presence of an agent or office” (8 CFR §214.2(l)(1)(ii)(H); 9 FAM 402.12-10(A)(b)).

- Minimum one-year employment abroad: The beneficiary-employee (‘transferee’) must have been working for a qualifying organisation abroad for a minimum of one continuous year within the three years immediately preceding the application/visa petition for US entry.

(See 8 CFR §214(1)(1)(ii)(A); CFR §214(1)(3)(iii); and INA §101(a)(15)(L).)

Specific L-1A and L-1B requirements: Aside from the above initial requirements, the employer must also satisfy specific L-1A and L-1B requirements.

L-1A managers and executives: For the L-1A visa category, the employer must also show that the beneficiary-employee will be employed in the United States in a managerial or executive capacity. For the purposes of the L-1A, ‘managerial capacity’ is defined as an assignment or role in which an employee primarily:

- manages the organisation, department, subdivision, function or component;

- supervises and controls the work of other supervisory, professional or managerial employees, or manages an essential function, department or subdivision within the organisation;

- has the authority to hire and fire or recommend personnel actions, or functions at a senior level within the organisation or as to the function managed; and

- exercises discretion over day-to-day operations of the activity or function.

‘Executive capacity’ is defined as an assignment or role in which an employee primarily:

- directs the management of the organisation or a major component or function;

- establishes the goals and policies of the respective organisation, component or function;

- exercises wide latitude in discretionary decision making; and

- receives general supervision/direction from higher-level executives (ie, board of directors, stockholders).

(See 8 CFR §214(1)(1)(ii).)

L-1B Specialized Knowledge: For the L-1B Specialized Knowledge visa classification:

-

the employer must establish that the beneficiary employee possesses either: -

- special knowledge of the employer’s product, service, research, equipment, techniques, management or other interests; or

- advanced knowledge of the organisation’s processes and procedures; and

- the visa petition must show that the employee has used that specialised knowledge in his or her employment abroad and will continue to use his or her specialised knowledge in the proposed US position.

6.4 What are the formal and documentary requirements to obtain a permit under this regime?

Qualifying relationship: To establish that the US employer and employer abroad are qualifying organisations, L-1 visa petitions must include corporate ownership or registration documentation showing that the foreign company is a parent, branch, affiliate or subsidiary of the US employer.

Doing business: L-1 petitions are usually accompanied by recent financial statements or tax documents showing that the organisation is doing business in the United States and at least one foreign country.

One-year employment abroad: L-1 visa petitions must also include proof that the beneficiary-employee was employed by the affiliate abroad for at least one continuous year within the last three years preceding application for entry into the United States. That proof could include pay statements covering one year of employment or year-end tax documentation. Any time spent in the United States will not be counted towards this requirement. Therefore, aside from pay statements or salary/income tax documentation, initial L-1 applications should contain all pages of the beneficiary-employee’s passport demonstrating the individual’s physical presence and employment abroad.

Specific L-1A and L-1B requirements: For L-1A visa cases, the petitioner must submit documentary evidence that the beneficiary-employee holds managerial or executive responsibilities, such as an employer statement and organisational chart(s).

For L-1B petitions, employers should submit documentation demonstrating the specialised knowledge held by the beneficiary, including but not limited to:

- an employer statement describing the transferee’s specialised or advanced knowledge;

- company-specific training completed or given by the employee on internal systems, tools, technologies or processes;

- patents or pending patents authored by the transferee;

- white papers authored by the transferee; and

- presentations on company-specific processes or technologies presented by the transferee.

6.5 What fees are payable to obtain a permit under this regime?

For most L-1 visa cases, the employer is required to pay a $460 petition processing fee to US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). In addition, employers must pay a one-time $500 dollar fee to support fraud prevention and detection. Employers with more than 50 employees in the United States are subject to an additional $4,500 fee if more than 50{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a} of their employees hold H-1B, L-1A or L-1B non-immigrant status. (See www.uscis.gov for current fees.)

The individual visa applicant must also pay a fee of $190 to the US consulate when applying for the actual visa. Applicants from certain countries are subject to additional visa fees depending on reciprocity agreements with the United States. (See www.uscis.gov for current fees.)

6.6 What is the process for obtaining a permit? How long does this typically take?

Obtain USCIS approval and secure visa stamp from US consulate: The first step in obtaining an L-1 visa is for the employer to file a petition with USCIS.

USCIS typically requires at least several months (potentially between eight and 10 months) to process L-1 petitions filed under regular processing (see USCIS regular processing times). A Premium Processing service for L-1 petitions is available for a fee of $2,500. USCIS will act on petitions filed under Premium Processing within 15 calendar days of receipt. However, if USCIS require additional evidence to adjudicate the petition, processing will be suspended until the petitioner furnishes the requested evidence.

If USCIS approves the L-1 petition, the employee can then schedule a visa interview with the US consulate in his or her jurisdiction. Once the employee passes the US visa interview and the US consulate completes its security/background checks, the US consulate will issue the L-1 visa stamp inside the employee’s passport.

Blanket L-1 petitions: US employers may apply for and participate in the Blanket L-1 visa petition programme. If USCIS grants the blanket, the US employer may transfer its employees to the United States by skipping the USCIS petition stage and having employees apply for their L-1 visa directly at a US consulate. This provides the employer with the flexibility to transfer employees to the United States quickly and easily.

To qualify for the Blanket L-1, the US employer must meet the following requirements:

- It has been doing business in the United States for more than one year;

- It has three or more domestic and foreign branches, subsidiaries or affiliates;

- Each qualifying organisation is engaged in commercial trade or services; and

-

It meets one of the following requirements: -

- Has obtained approvals for at least 10 L-1 petitions in the past 12 months;

- Has US subsidiaries or affiliates with combined annual sales of at least $25 million; or

- Has a US workforce of at least 1,000 employees.

For eligible employers, Blanket L-1 approval greatly improves their ability to quickly transfer qualified L-1 applicants to the United States.

(See 8 CFR §214(1)(4) and (5).)

7 New hires

7.1 Are employers in your jurisdiction bound by labour market testing requirements before hiring from overseas? Do any exemptions apply in this regard?

For the vast majority of US work visas, employers are not required to test the labour market before hiring from overseas. However, certain short and long-term work visas require a labour market test:

- H-2A and H-2B temporary work visas for agricultural workers and non-agricultural workers respectively; and

- US permanent residency/green card pathways under the EB-2 Advanced Degree or EB-3 Professional or Skilled Worker (Program Electronic Review Management (PERM) based) immigrant visa preference categories.

7.2 If labour market testing requirements apply, how are these satisfied and what best practices should employers follow in this regard?

The US Department of Labor (DOL) has a set of labour market testing requirements for employers sponsoring those mentioned in question 7.1 For example, employers intending to sponsor current or prospective employees for long-term or permanent employment by means of green card sponsorship under the EB-2 and EB-3 PERM-based categories must meet the following requirements:

- Meet all DOL posting and advertising requirements within a 180-day period, to include posting the job opportunity through six different media sources (eg, employer posting notice(s), state workforce agency website, newspaper of general circulation) within the area of intended employment;

- Conduct good-faith recruitment efforts, demonstrating that there are “not sufficient US workers able, willing, qualified and available” for the job opportunity, even “within a reasonable period of on-the-job training”; and

-

Comply with all DOL employer obligations surrounding the labour certification application for permanent employment.

(See 20 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) § 656.17.)

Employer best practice: The DOL’s job is to protect the jobs of US workers. Therefore, employers are strongly encouraged to conduct all recruitment efforts in good faith and full compliance with DOL regulations. The DOL will conduct employer audits at random (though audits tend to increase when the economy is slow) and where an employer is suspect of any fraudulent, misrepresentation or non-compliance.

7.3 Which work permits are primarily used for new hires? What is the process for obtaining them and what fees are applicable, for both employer and employee?

Below is a list of work visas that are typically used for new hires. Each of these visas requires the sponsorship of a US employer, which acts as the ‘petitioner’ on the application. The process for obtaining the visa will depend on whether the individual is abroad or already in the United States.

Applying from abroad: Applicants for certain visa types (E-3, H-1B1 and TN) may apply for the work visa directly at a US consulate in their local jurisdiction. However, for those seeking H-1B, H-2A, H-2B, O-1 or P visa classifications, the petitioning US employer must first secure approval from US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) by submitting a Form I-129 petition. Once the visa classification is approved by USCIS, the prospective employee may then apply for a visa stamp at a US consulate in his or her local jurisdiction.

Applying while in the United States: In certain cases, where a prospective employee is already lawfully studying/working and living in the United States, it is possible that the prospective employee may not need to depart the United States and may instead be eligible to change or transfer his or her immigration status to the visa classification sponsored by the petitioning US employer. In such cases, the US employer need only file the visa petition with USCIS.

|

Visa type |

Fees |

|

E-3 Australian Professionals |

|

|

H-1B Professionals |

|

|

H-1B1 Chile/Singapore Professionals |

|

|

H-2A Seasonal Agricultural Workers |

|

|

H-2B Seasonal Non-Agricultural Workers |

|

|

O-1 Extraordinary Ability |

|

|

P-1/2/3 Athletes/Artists/Entertainers |

|

|

TN Canadian/Mexican Professionals |

|

7.4 Is labour market testing required if the new hire is to extend his or her residence?

Yes, both the H-2A and H-2B classifications require a new labour market test if the US employer chooses to request an extension of the new hire’s stay/work permit. Once the employer has secured a new and valid temporary labour certification covering the requested period of extended stay, the employer may then petition an extended H-2A/2B on behalf of the new hire.

7.5 Can new hires apply for permanent residence?

New hires on certain ‘dual intent’ work visas (eg, the H-1B and L-1) may apply for US permanent residence. In certain situations, new hires on single ‘non-immigrant intent’ only work visas may commence the US permanent residence application process but will face international travel limitations during the application process; therefore, employers should consult immigration counsel on the best pathway to US permanent residency for new hires.

8 Sponsorship

8.1 Are any licences or authorisations required to sponsor foreign nationals? What other criteria apply in this regard?

All US employers are eligible to sponsor a foreign national for a work visa/permit, provided that the employer:

- is doing business in the United States;

- has a valid job offer; and

- meets all employer obligations under the respective visa.

8.2 What obligations do sponsoring employers have to ensure continued immigration compliance?

In general, sponsoring employers must meet the following requirements:

- Have/intend to have a bona fide job offer at the time of filing the visa petition on behalf of the sponsored employee;

- Have/maintain a job offer for the duration of requested stay (in some cases, such as where a H-1B visa employee is terminated before the end of H-1B validity period, the employer is required to pay for the employee’s return trip home);

- Pay at least the offered salary listed on the visa petition (for certain visas, such as H-1B and E-3, the employer must pay a salary meeting the area of intended employment prevailing wages as determined/approved by the government);

- Pay the legal and/or government fees associated with certain visas (H-1B, labour certification for permanent residency);

- Meet all conditions specified in the US Department of Labor (DOL) certified labour condition application (LCA) (ie, the employee is being paid the wages promised in the application and is working in the occupation and at the location specified); and

- File the visa petition/application in good faith.

8.3 Are sponsoring employers subject to any local training requirements?

No.

8.4 How is compliance with the sponsorship regime monitored? What are the penalties for non-compliance?

As explained in question 1, there are various US government agencies with jurisdiction over the US immigration lifecycle, depending on the type of application (see also questions 3, 4 and 7). For example, the DOL will conduct audits randomly and/or when it suspects fraud or misrepresentation – typically with respect to labour certifications for permanent residency. Likewise, the US Department of Homeland Security’s Fraud Detection National Security Directorate will conduct onsite, in-person audits and/or telephonic interviews randomly and/or when any fraudulent or misrepresentation activity is suspected, typically pertaining to the H-1B work visa. Similarly, the US Department of State will conduct random security/background checks when an individual is applying for a visa from abroad; the interviewing officer is tasked with exploring or identifying any detection of fraud/misrepresentation during the interview and application review.

Penalties for non-compliance should be taken seriously. For example, where an employer violates the conditions of an LCA – typically associated with H-1B, H-1B1 and E-3 visas – civil penalties will apply for each violation ($1,848 to $52,641 per violation), plus other remedies, including the payment of back wages. In addition, an employer’s immigration programme can be completely barred from any future visa sponsorship for a period of at least one year (see 20 Code of Federal Regulations §655.810; DOL Wage and Hour Division, Field Operations Handbookat 71e). Therefore, an employer should always make good-faith efforts to remain compliant with all visa requirements, given the overall business consequences – both financial and reputational – of breach.

9 Trends and predictions

9.1 How would you describe the current immigration landscape and prevailing trends in your jurisdiction? Are any new developments anticipated in the next 12 months, including any proposed legislative reforms?

While extreme and harsh immigration measures were quickly implemented and arbitrarily applied under the former administration’s “Buy American, Hire American” policy, the current Biden administration has made clear its intent “to restore faith in the legal immigration system” and “believes that one of America’s greatest strengths is [its] ability to attract global talent to strengthen [the US] economy and technological competitiveness”.

As a result, we can expect not only continued restoration of a more transparent and consistent decision-making process, but also modernisation of the adjudicating agency’s application of law, with a particular emphasis on attracting global science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) talent to strengthen the US economy and technological competitiveness.

Already, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has announced that it will be updating adjudication manuals “to advance predictability and clarity” for the hiring of STEM global talent that will contribute to US “scholarly, research and development, and innovation communities”. The changes include:

- the addition of 22 new fields – primarily new multi-disciplinary or emerging fields – to the two-year STEM Optional Practical Training work permit available to qualifying F-1 students after completion of their US degree in the qualifying STEM field;

- examples of evidence that will satisfy the O-1 Extraordinary Ability visa, particularly for those whose field of expertise is STEM-related; and

- clarification of how individuals with advanced degrees in STEM fields can leverage the EB-2 National Interest Waiver green card process.

(See White House Fact Sheet, 21 January 2022.)

In addition, the DHS, in coordination with the US Department of State (DOS), is committed to adjudicating as many employment-based green card application to ensure that no green card ‘visa’ is ‘unused’ in FY 2022. An “exceptionally high number” of employment-based green card visas are available due to the effects of past visa travel bans and extreme visa backlogs originating from the prior administration. In demonstration of its commitment, US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) implemented a process in late January 2022 in which an applicant can revert a pending green card application to the EB-2 preference category in order to take immediate advantage of the excess green card visa availability (see USCIS interfile guidance.)

Finally, the House of Representatives recently passed a bill, the America COMPETES Act of 2022, in furtherance of the administration’s efforts to strengthen the nation’s economy and competitiveness. The bill – which still awaits Senate approval before it reaches the president’s desk – includes two significant immigration-related measures designed to boost the country’s innovation:

- a direct green card pathway for foreign PhD graduates of US universities in the STEM fields, exempting this group from the longstanding annual numerical green card visa limits applied to all foreign nationals; and

- a temporary visa (‘start-up visa’) for foreign entrepreneurs.

10 Tips and traps

10.1 What are your top tips for businesses seeking to recruit talent from abroad and what potential sticking points would you highlight?

- Recruiting global talent who are physically abroad may present logistical and timing challenges given the current political and health climate. These variables create uncertainty in the timeliness of securing a visa. Therefore, when recruiting global talent from abroad, employers must remain flexible.

- Because of logistical concerns and the unpredictability of the current political and health climate, hiring global talent who are already physically in the United States is typically and relatively a simpler and quicker process, which affords a greater degree of certainty for employers.

- If hiring a F-1 student graduating from a science, technology, engineering or mathematics (STEM) or non-STEM field, consider registering the employee in the H-1B cap lottery to ensure continued authorisation of employment with your company beyond the expiration of the F-1 work permit.

- Consider employer green card sponsorship as a recruiting/retention tool.

- Take US visa compliance rules and regulations seriously (see question 8).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.