Germán Cadenas was 15 when he packed up a few clothes, his beloved magic trick cards, a treasured coin box and a portfolio of his drawings.

It was 2002. Cadenas, his mother and younger brother were flying from their native Venezuela for a Christmas visit with Cadenas’s dad – who had migrated to Maricopa county, Arizona, two years before – hoping to send money to his family as Venezuela descended into chaos.

Reunited in Arizona over the holiday, the family decided what mattered most was staying together. They let their visas expire and settled in.

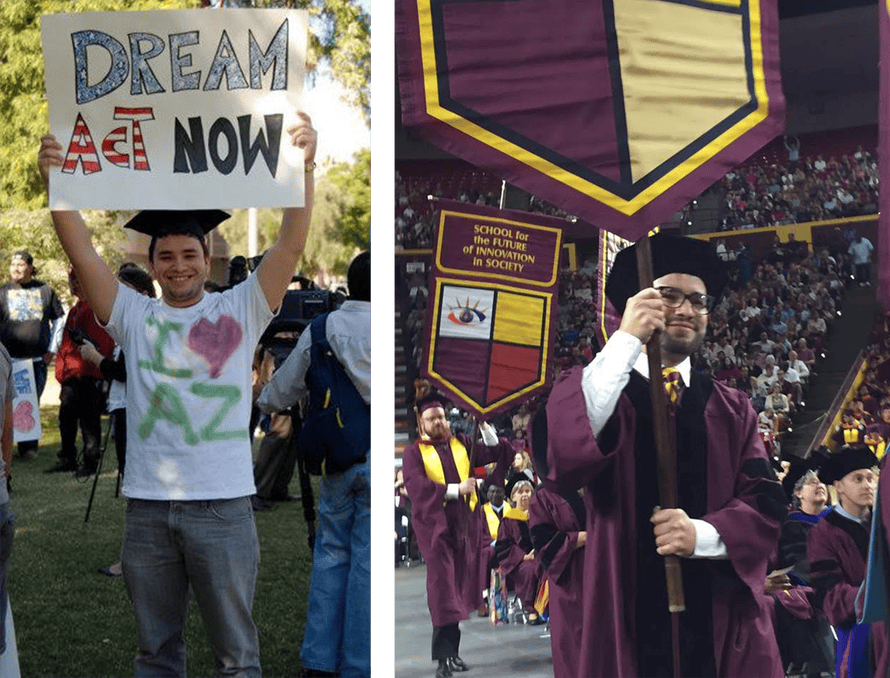

Cadenas lived in Arizona as an undocumented immigrant for nine years. Nearly 10 years later, he’s 34 and a US citizen. He’s a professor of psychology at Lehigh University, and has published a prodigious body of research focusing on the psychology of undocumented immigrants.

For at least a decade, researchers have documented mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, PTSD and feelings of low self-worth in America’s immigrant communities.

Such mental health issues can stem from being marginalized, hunted and detained as well as from feeling dehumanized by xenophobic rhetoric, an exclusionary higher educational system, predatory employment practices, civil rights violations and the uncertainties of changing immigration policies, researchers and advocates say.

It’s impossible to accurately say how many of the nation’s approximately 10.5 million undocumented immigrants and their family members are living with mental health issues tied to their immigration status. But the number of those afflicted is likely to increase as the climate crisis and geopolitical unrest drive more migrants to cross the nation’s borders.

In Arizona, the epicenter of the US’s immigration wars, those who have experienced such traumas first-hand have also pioneered ways to respond to it and are training others seeking to treat it. The stories of Cadenas and other immigrants in Maricopa county illustrate the power of activism to reshape trauma and cope with it.

Cadenas has focused his research on a psychological construct called “critical consciousness”. He’s found that when immigrants identify systems that psychologically harm them and then engage in social justice activism to resist and dismantle those same systems, their efforts serve as a “coping mechanism that helps protect their mental health” and helps others heal.

Cadenas’s interest in the topic stems from experience. His family settled in the Grand Canyon state at the very time it started to became overtly hostile to undocumented immigrants and their American citizen relatives.

Amid congressional paralysis on immigration reform, Arizona was just beginning to pass a series of immigration laws intended to either criminalize undocumented immigrants with deportable felonies or make their lives so miserable, they would leave the state.

Meanwhile, Maricopa county’s sheriff, Joe Arpaio, partnered with federal authorities to conduct shock-and-awe immigration sweeps. Knowing how to capture the national spotlight, the sheriff also dispatched swarms of armed deputies to arrest undocumented immigrants traveling through the state or to raid workplaces in search of deportable workers.

“It felt like nowhere was really safe,” Cadenas recalls. “We could be raided at work, or stopped while driving or Ice could come to our home. There was no place of refuge.”

“Knowing there were laws and voters who were OK with this was horrifying,” he says. “People like me were treated as if we were less than human.”

Cadenas became an activist, publicly opposing the sheriff and state immigration laws while advocating for affordable in-state tuition for undocumented college students and the passage of the Dream Act, which would provide a pathway to citizenship for law-abiding people who arrived in the US at a young age.

This activism, he says, improved his psychological wellbeing. It gave him pride in his “culturally rich” and “resilient” Latinx immigrant community. The activism helped him understand he mattered.

Through his activism, Cadenas met other young immigrants who were coping with similar traumas.

Viri Hernández and her mother Rita have been immigrant rights activists for well over a decade.

Now 30, Viri is the executive director of the Phoenix immigrant civil rights non-profit Poder in Action. When she first got into activism, her mother cooked and chauffeured her and other young activists to marches and demonstrations. Gradually, Rita became more involved.

Once, Viri and Rita helped block a major Phoenix street near an Ice office. The act of civil disobedience landed them both in Arpaio’s jail – a stay Rita mostly remembers for its bad food, icy temperature and Ice authorities telling her she had no civil rights.

Rita was born in Morelos, Mexico, and was forced to marry Marcos, the father of her unborn child, at 17. The pair struggled, Rita says, trying to make a dysfunctional marriage work while living in extreme poverty. Their baby, a girl, died three days after being born prematurely because medical personnel in the area had no available incubator, she says.

Viri, short for Viridiana, was born in 1991. About a year later, mother and daughter crossed the US-Mexico border, Rita says, joining relatives already settled in Maricopa county.

Marcos followed six months later. The couple set down roots in Phoenix and would eventually have five more kids, all American citizens.

The Hernández clan was now officially a “mixed-immigration-status” family in which all family members, regardless of immigration status, would experience trauma.

In 2012, sheriff’s deputies raided the construction company where Marcos, a carpenter, worked. He’d clocked in early that day and was already out on a job when the raid took place, but he feared the deputies had checked his employment file and now knew where he lived.

The family considered fleeing the state, but instead moved to a hidden corner of the county.

“Nothing has ever been easy,” Rita says. Her own upbringing and journey to the US was rough. Her kids grew up terrified authorities would snatch their parents and are still working through that trauma.

But successful activism has lifted her spirit and diminished her anxiety, Rita says.

After being released from her short stint in jail, Rita dedicated herself to full-time social justice organizing and educating undocumented immigrants about their civil rights. She helped organize a voter outreach effort, risking getting stopped by sheriff’s deputies during her daily 90-mile-round-trip commute. But it paid off, she says. Arpaio was voted out of office in 2016, proving that undocumented immigrants have a powerful voice.

Rita, who is now 49, serves as a leader at Poder in Action, where she organizes with her daughter. The non-profit aims “to disrupt and dismantle systems of oppression and determine a liberated future as people of color in Arizona”.

There are some things, though, that even activism cannot begin to heal. Every day of the dead, Rita puts on an ofrenda with Virgin of Guadalupe candles lighting up framed pictures of dead relatives, including the baby she lost. As an offering to the soul of the child she still grieves, she bakes bread in the shape of a doll, and sets it on the table along with a small container of yogurt, a glass of milk and a See’s Candy Lollypop.

Like Viri Hernández and Germán Cadenas, Reyna Montoya was heavily involved in Arizona’s immigrant activist community as a student. But she struggled to find a community she felt aligned with.

Montoya had joined Arizona’s immigrant activist community in 2010, after she came out publicly as an undocumented college student. She was already “heavily involved” when her father Mario, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico, was detained by immigration authorities at a Puerto Rico airport in 2012.

Mario had fled from Mexico to Arizona with his family in 2003 after he had received death threats and was kidnapped by corrupt members of Mexican law enforcement, Montoya knew. Now he sat in a Puerto Rican prison in an Ice unit facing deportation by the Obama administration. Should he be deported to Mexico, his family in Phoenix feared, he’d be murdered.

Arizona’s immigrant community rallied on her father’s behalf, Montoya says. But “no one asked me, ‘How are you doing? What does it mean for you to have your dad in deportation proceedings?’ That really hurt, although I understand. People who were hurting were hurting others. If you haven’t processed your own traumas, the cycle continues.”

In 2016, Montoya founded Aliento, a Phoenix non-profit that she started with a Soros Fellowship and her desire to create a gentle, culturally sensitive healing environment for undocumented immigrants and their families.

Aliento is housed in a cheerful Phoenix office building with large windows that look out on to cactus gardens. The non-profit connects immigrants struggling with trauma with Spanish speaking therapists. It also focuses on training young leaders. You probably will not find Aliento fellows blocking streets in civil actions, even though they, too, focus on changing policies that are harmful to undocumented immigrants.

Aliento was key in getting on the 2022 ballot a measure that will let voters decide whether to grant in-state tuition and scholarships to all Arizona high school graduates regardless of immigration status, students often known as Dreamers.

Montoya and her partner, José Patiño, the education and external affairs director for Aliento, are Dreamers themselves.

They have temporary protection from deportation through Daca, an Obama-era permit for Dreamers that some conservatives hope to dismantle in the courts.

Now 30, Montoya recently turned in her sixth Daca renewal application. The possibility of her application getting lost in the shuffle fills her with anxiety. Without Daca, she would become an unprotected, undocumented immigrant once again.

After years in deportation proceedings, Montoya’s father was granted political asylum in 2019, Montoya says.

The Daca program that protects her was started by the Obama administration, which also put her father into deportation proceedings. She’s grateful for Daca, yet traumatized by the deportation nightmare. She wonders sometimes if she’s “the only person who thinks Obama has done bad things”.

Maybe it’s a mistake to assume those who have experienced immigration trauma seek closure, she says. Maybe what they want instead is a simple “acknowledgment that harm was done”.