The plan to shut down Rikers Island, funding for violence-interrupter groups and criminal data analysis all fall under the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, commonly referred to as “MOC-J.”

During the pandemic, the office has also collaborated with prosecutors, defense attorneys and court officials to identify detainees in city jails who could be let out early under supervised release.

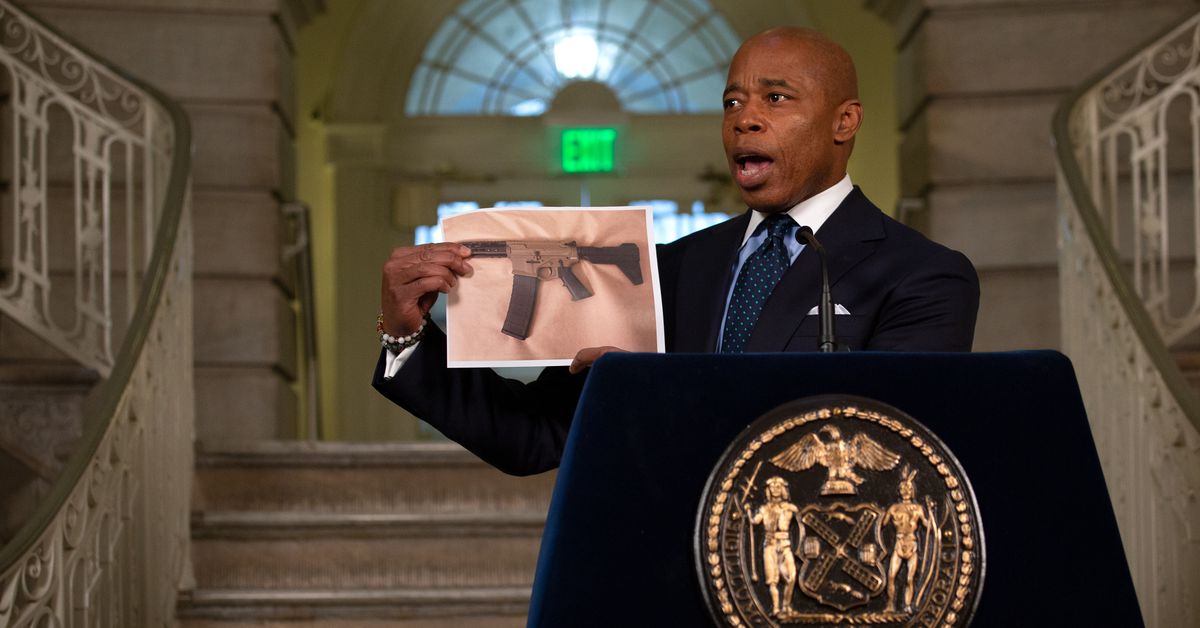

But Mayor Eric Adams, who has publicly declared crime prevention a top priority, has not yet named the head of MOCJ, making it a key spot still vacant.

At stake is how the Adams administration will handle calls for criminal justice reforms — some already in motion — while pursuing his tough-on-crime agenda. Experts and advocates contend that simply arresting more people and making it harder for them to post bail is not the long-term solution.

“MOCJ is truly the agency that pulls together all of the resources of the city and service providers and community-based organizations,” said Jullian Harris-Calvin, director of the Greater Justice New York program at the nonprofit Vera Institute.

“And so when there isn’t someone who is at the helm of that agency, it really hampers the city’s ability to address crime and violence without merely relying on traditional policing,” she added.

In January, the former head of MOCJ since Oct. 2020, Marcos Soler, left to become the state deputy secretary for public safety.

New Deputy in Town

Administration officials declined to comment on the record for this story and have not disclosed who has been interviewed for the post or the hiring timeline, as speculation over who may be appointed to the post has intensified.

Ingrid Lewis-Martin, Adams’ deputy borough president in Brooklyn, was considered for the post before he named her chief advisor, according to a former MOCJ official.

Adams meanwhile has touted the creation of a Deputy Mayor for Public Safety role headed by his longtime close ally and former top NYPD official Phil Banks.

During the transition, Banks, an unindicted co-conspirator in a major NYPD-tied corruption case, interviewed police and correction commissioner candidates as he worked out of an office at 1 Police Plaza.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23241611/adams_banks.jpg)

“It’s very unclear what’s going on,” said a City Hall insider. “There’s a fight over who will control MOCJ and what role it will play.”

On Monday, Adams met with top state lawmakers to make his case for more funds and legislative changes to recent reforms to bail laws and prosecutions of 16- and 17-year-olds charged with gun crimes.

The mayor has also called for increasing the budget to assist people with mental illness.

“I feel I have partners that want to help not only New York City, but help the state,” he told reporters after meeting with State Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins and State Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie.

Cure Violence Groups in the Middle

Before leaving office, the de Blasio administration put out a call for proposals seeking to expand the “cure violence” program of interrupters to additional precincts where crime has spiked.

The submissions were due in mid December and city officials are currently reviewing the applications.

Cure violence groups are contracted by MOCJ to prevent deadly conflicts in their communities and generally help keep the peace. They are required to file monthly reports to the office detailing how many encounters they’ve had and multiple other metrics.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22767127/AdvancePeace_01.jpg)

Adams, a former NYPD captain, has touted the program as a key element to his broader plan to drive down crime. One of his first moves was to meet with the leaders of multiple interrupter groups in the city. He also talked about the model, first started in Chicago, during his meeting this month with President Joe Biden.

But many police officials are not fans of the initiative, citing a lack of trust in some formerly incarcerated leaders of the CV programs. Cops complain the violence interrupters often don’t share information they may have about a crime — because they don’t want to be seen as snitches.

‘Moral Authority’ and Coordination

The lack of a MOCJ leader leaves the contract oversight — and the selection of possible new groups — in the lurch, agency insiders said.

During most of the de Blasio administration, MOCJ was helmed by Liz Glazer, a former federal prosecutor with decades of experience and a keen focus on tracking statistics to show results.

Over the past decade, the agency vastly expanded.

The budget increased from $275 million in fiscal year 2011 to $813 million budgeted in fiscal year 2023, according to the city’s Independent Budget Office. The number of vendors receiving criminal justice contracts over the same period has gone from 58 in fiscal year 2011 to 194 in fiscal year 2021, the IBO said.

“She hugely increased the size of the place,” said Michael Jacobson, who served as commissioner of the Departments of Probation and Correction commissioner under former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani.

“They have a really substantial analytic capacity and increased the amount of money it funds for organizations that do things like supervised release and violence interrupters,” he added.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20024948/060820_city_hall_worker_protest_7.0.jpg)

Glazer and her staff issued reports supporting bail reform and the “Less is More” legislation to give parolees more leeway in avoiding jail after being busted for low-level offenses or technical violations.

The head of MOCJ has a staff of roughly 60 city employees but doesn’t have official sway over the court system or the city’s five prosecutors, Jacobson noted, calling it a “finesse position.”

“You have to be seen as someone that has the legitimacy and moral authority to do all sorts of coordination and projects,” he said.

An ‘Engine of Reform’

MOCJ has taken the lead role in overseeing the $8 billion plan to shut down Rikers Island and replace the facilities there with four, smaller, more modern jails in each borough except for Staten Island.

Dana Kaplan, MOCJ’s director of the Close Rikers and Justice Initiative, is currently out on maternity leave. Nadine Maleh, the agency’s executive director of capital projects, is playing a key role in the plan.

The shutdown plan calls for reducing the jail population to around 3,544. During the peak of the pandemic, the population dropped to below 3,900 for the first time in decades in April 2020, records show.

MOCJ led the way for expedited releases by generating a list of detainees who could qualify. The agency pushed the NYPD and prosecutors to approve those people and worked with a court system operating remotely to make it happen. MOCJ leaders also pressed state prison officials to release people held on technical parole violations such as missing curfew or failing a drug test.

There are now 5,665 people behind city bars, slightly more than before the pandemic, according to Correction Department data posted online. Inmate advocates are pressing the city to once again reduce the population, citing an explosion of violence and delayed medical care.

MOCJ under the de Blasio administration also supported “Raise the Age’’ legislation out of Albany. The measure, passed in 2017, stops 16 and 17-year old children from being automatically prosecuted as adults.

Adams is now seeking to pare back that law, arguing some teens are being used as pawns by older criminals seeking to evade punishment.

The mayor now contends teens facing weapons charges who refuse to say where they got a gun from should be prosecuted as adults, although in 2017 he supported the original measure.

“It’s incredibly important that the city does get a director of the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice,” said Harris-Calvin, “because that is the engine of public safety and criminal justice reform in the city.”