The House may soon vote on Democrats’ $1.75 trillion budget reconciliation bill, with provisions to shield undocumented immigrants living in the US from deportation and relieve long visa backlogs.

But like many of the immigration proposals from the last few decades, these new, critical immigration fixes appear unlikely to actually become law. So why is this latest round of immigration reform proposals probably doomed? Two reasons: because of the structure of the Senate and because, on immigration, identity issues have replaced policy.

The American public has never been more supportive of immigration, with a third saying that it should be increased. In 1986, the last time Congress passed a major immigration reform bill, only 7 percent of Americans supported increasing immigration levels. And narrower reforms, such as expanded protections for undocumented people already in the US, have been found to have majority support.

But despite that growth in public support, the House and Senate haven’t been able to reach bipartisan agreement on immigration in decades. Though comprehensive immigration reform bills passed one chamber in 2007 and 2013, they ultimately failed in the other. And while the House has passed bipartisan legislation addressing narrower immigration issues over the last couple of years, those bills have yet to gain traction in the Senate.

This has led to a Democratic insistence on trying to use the budget reconciliation process to address immigration, which would bypass the need for Republican support. So far, those efforts have failed. But Democrats haven’t given up on it yet.

As part of their social and climate spending package, known as the Build Back Better Act (BBB), Democrats initially sought to create a path to citizenship for millions of undocumented immigrants living in the US. That plan was rejected by the Senate parliamentarian Elizabeth MacDonough, who is tasked with determining what can and cannot be passed via budget reconciliation.

Reconciliation allows bills to pass the Senate with a simple majority — which Democrats have by one vote — but for a provision to be included in a reconciliation package, it must have a “more than incidental” impact on the budget. A pathway to citizenship, MacDonough said, would be a “tremendous and enduring policy change that dwarfs its budgetary impact.” Democrats then proposed giving people who entered the US illegally prior to 2010 a pathway to green cards. MacDonough also nixed this plan.

This has led to Democrats’ plan C. Under the latest draft of the bill, undocumented immigrants would be given temporary protection from deportation through what is called “parole” for a period of five years. Those who arrived in the US prior to 2011 — numbering an estimated 7 million — could apply for five-year, renewable employment authorization.

The bill would also recover millions of green cards that went unused in the years since 1992. Under current law, any allotted green cards not issued by the end of the year become unavailable for the following year. In 2021, the US failed to issue some 80,000 green cards due to processing delays, and those cards have now gone to waste.

The bill also allows some people who have been waiting to be issued a green card for at least two years to pay additional fees to bypass certain annual and per-country limitations and become permanent residents years, if not decades, sooner than they would have otherwise. And the bill preserves green cards for Diversity Visa winners from countries with low levels of immigration to the US who were prevented from entering the country on account of Trump-era travel bans and the pandemic.

Those provisions, though short of desperately needed structural reform to the immigration system, would provide long-awaited assurance for many undocumented immigrants who have put down roots in the US and more opportunities for legal immigration at a time when the country could use more foreign workers. The provisions are also broadly popular: A recent poll from Data for Progress found that 75 percent of voters, including a majority of Republicans, back them.

Nevertheless, they may be on the chopping block.

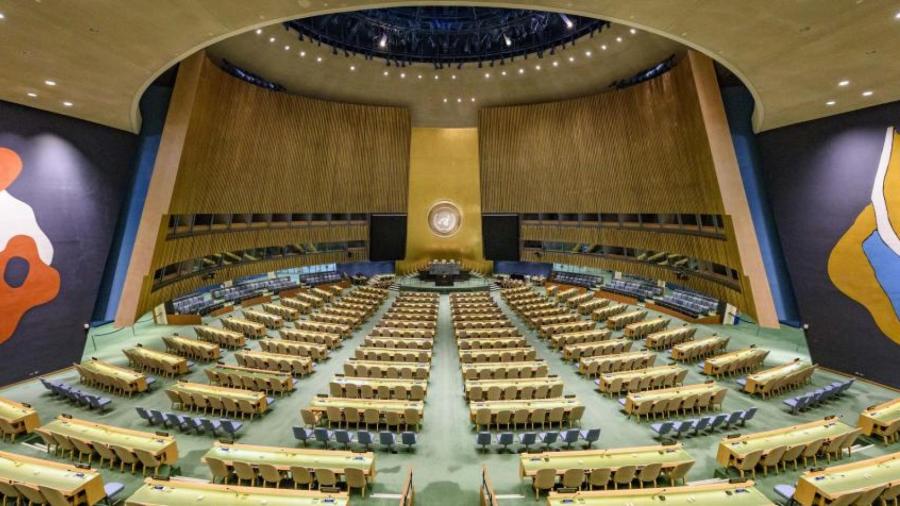

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23009805/GettyImages_1346388905.jpg)

Democrats’ immigration proposal faces potential roadblocks in the Senate

In the House, Reps. Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, Adriano Espaillat, and Lou Correa have pushed for immigration reforms to be included in the reconciliation package. But even if they are ultimately successful, the provisions face two significant obstacles in the Senate: key moderates and the parliamentarian.

Moderate Sen. Kyrsten Sinema announced last week that she supported the current provisions, but there is no word yet from Sen. Joe Manchin, who has expressed skepticism about addressing immigration in the bill. As Senate Democrats need every vote in their caucus, should Manchin refuse to back the provisions, they’d be effectively dead.

MacDonough has also yet to weigh in on the latest plan. But given that she twice rejected Democrats’ previous immigration proposals, she may do so again. Explaining why she rejected Democrats’ path to citizenship proposal in September, MacDonough wrote that the impact of the legislation far outweighed its budgetary consequences, making it inappropriate to include in a reconciliation bill.

“It is by any standard a broad, new immigration policy,” she said. “The reasons that people risk their lives to come to this country — to escape religious and political persecution, famine, war, unspeakable violence, and lack of opportunity in their home countries — cannot be measured in federal dollars.”

She also asserted that, if she were to allow Democrats to pass the measure through reconciliation, that might be used as a precedent to justify revoking any immigrants’ legal status in future reconciliation bills.

Proponents of including immigration in reconciliation have asserted that MacDonough might take a different tack when it comes to plan C, in part because it doesn’t create any new, permanent legal protections that weren’t previously authorized by Congress. But her September opinion suggests that she opposes any use of reconciliation that has far-reaching consequences for immigrants.

“No one can be categorically sure about what she’s going to do. But there’s enough in her opinion to suggest that she will think this was too big a reach in reconciliation,” said Muzaffar Chishti, a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank.

Despite calls to overrule — or even fire — the parliamentarian, Democrats have made it clear they plan to abide by her ruling. As Democratic Sen. Bob Menendez said in a September press call, “The parliamentarian is the final word of what is and not permitted under the rules.”

Congress hasn’t passed major immigration legislation in two decades

These barriers mean immigration reform seems to be proving elusive once again. Experts say that’s because immigration has shifted from a matter of policy to a matter of identity, and that as this shift was happening, the way Congress functions changed drastically.

Chishti said that the immigration debate previously used to be principally focused on ideas: “Is immigration good for the country or not? What kind of immigration is good for the country — high-skilled, low-skilled? Do we need more finance people or more nurses?”

And there used to be immigration proponents — and skeptics — in both parties. For instance, labor unions used to advocate for restrictionist immigration policies, though that shifted in the 2000s. Business-minded Republicans recognized the economic benefits of immigration. Now, the debate is more tied up in identity. It has also grown in electoral importance, with voters ranking it the third most important issue facing the country after the coronavirus and the economy in a Harvard CAPS-Harris poll earlier this year.

“Immigration is all about culture and race. It is about people’s perception of how immigration is changing our country,” Chishti said. “It’s much more emotional.”

What has also changed is Congress’s reliance on the filibuster. During the era in which the 1986 bill was passed, you could “count on one hand the number of times the filibuster was invoked,” Chishti said. Now, if a majority in the Senate doesn’t support legislation, it doesn’t even get considered.

That makes it hard, but perhaps not impossible, to build consensus around immigration.

Should their efforts to include immigration in the reconciliation bill fail, Democrats might not have another chance to pursue their policy priorities until after next year’s midterms — and that’s assuming they maintain control of both chambers of Congress, a scenario that’s very much in doubt. A Republican Congress may not be interested in immigration reform at all, especially if they intend to use immigration as an electoral weapon against the Biden administration and the Democratic party.

Regardless of who controls Congress in 2023, there might be room for compromise on narrower reforms to the legal immigration system that relate to the economy, according to Theresa Cardinal Brown, managing director of immigration and cross-border policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

A Bipartisan Policy Center-Morning Consult poll conducted in May found that, across the political spectrum, people were more likely to be willing to compromise on the issues of “providing visas for immigrants supporting the US economy where companies cannot find US workers” and “providing visas for immigrants investing in research and innovation for future growth of the US economy.”

While those issues don’t represent the top priorities of either party on immigration, addressing them might have important corollary impacts. Creating new legal pathways for foreign workers might mitigate unauthorized immigration at the southern border and also open opportunities for undocumented immigrants already living in the US to get legal status.

“If we legalize everybody in the country tomorrow, we still have the same system in place that made them become undocumented,” Cardinal Brown said. “What do we do with the next person? Unless we fix our legal immigration system, we’ll continue to be in that position.”