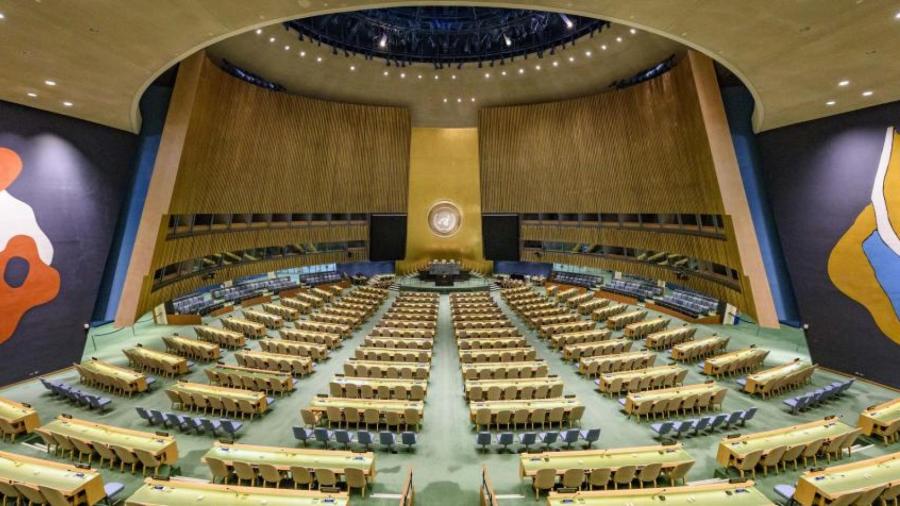

(November 22, 2021 / JNS) The Fourth (Special Political Committee) of the United Nations General Assembly’s 76th Session voted on Nov. 9 to adopt a draft resolution titled “Assistance to Palestine refugees.”1

This resolution, adopted annually for more than 70 years, calls inter alia for continued assistance for Palestinian refugees and continued support for the work of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA).

The resolution was adopted by a recorded vote of 160 in favor and 1 against (Israel), with nine abstentions (Cameroon, Canada, Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, United States and Uruguay).

In this vote, the United States changed its traditional opposition to the draft resolution and abstained. In fact, the United States’s voting history regarding this resolution indicates that all previous administrations, apart from the Obama administration, have voted against this resolution.

In his explanation of the vote in the Fourth Committee of the U.N. General Assembly in 1999, the U.S. representative (representing the Clinton administration) stated, “his delegation could not support unbalanced resolutions which attempted to prejudge the outcome of negotiations; lasting peace would come from agreements reached among the parties themselves, not from any action taken by the Committee.”2

This position was reaffirmed in 2003 under the George W. Bush administration by the U.S. Fourth Committee representative, who stated that the United States “had not voted in favor of several resolutions on that subject (humanitarian assistance) because it judged that they (…) were drafted in terms that could have repercussions on the peace negotiations in the region.”3

Finally, the same position was taken recently—even more assertively—by Cherith Norman Chalet in the Fourth Committee in 2019, during the Trump administration, who stated: “ … such a one-sided approach damaged the prospects for peace by undermining trust between parties. It was disappointing that, despite the support for reform, member states continued to single out Israel.”4

A wrong interpretation

The international and Israeli media pounced on this change in the U.S. voting pattern, erroneously claiming that it signified “support by the Biden administration for a right of return for Palestinian refugees to sovereign Israel.”5

In fact, the U.S. vote-change signifies no such thing, and the resolution does not mention any right of return for Palestinian refugees. Therefore, the U.S. abstention implies no support for a right of return.

In light of this erroneous perception arising from flawed and inaccurate media reporting, there is a need to clarify the issue of whether any such right of return exists.

A brief overview

The issue of Palestinian refugees has been seen as a principal obstacle to a conflict-solution between Israel and the Palestinians for more than 70 years. The situation originated during the 1946-48 period when local Arab residents were displaced or chose to relinquish their homes during the course of armed conflict. In order to support those refugees, UNRWA was established in 1949 with a budget of $50 million.6

As of today, UNRWA supports some five million registered Palestinian refugees. However, the UNRWA definition of refugees is considerably broader than the internationally accepted definition of refugees according to the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951),7 inasmuch as UNRWA includes descendants of refugees. Descendants are not included in the 1951 Refugees Convention.8

Does a “right of return” for Palestinian refugees exist in international law?

Several international legal and political documents try to tackle the difficult situation of return for refugees. But they do not appear to establish any right of return for Palestinian refugees.

I. U.N. General Assembly Resolution 194 (III)9

Resolution 194 (III) is the first major U.N. General Assembly Resolution that refers to the Palestinian refugees. Even though the Arab states initially strongly opposed Resolution 194 (III), claims to a right of return are now mainly based on this text. The resolution was adopted on Dec. 11, 1948, by a vote of 35 (including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and European states) in favor, 15 (six Arab League states—Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and Yemen, together with the USSR and its satellite states) against, and eight abstaining.10 With this resolution, the General Assembly established a three-state Conciliation Commission for Palestine11 and instructed it to “take steps to assist the Governments and authorities concerned to achieve a final settlement of all questions outstanding between them.”12

Paragraph 11 of the Resolution addresses the situation of refugees. According to the paragraph, “refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return.”

This paragraph neither establishes nor recognizes any right. In fact, no resolution of the General Assembly has the capacity to determine laws or establish rights. The resolution recommends that refugees “should” be “permitted” to return. The word “should” underlines that this is solely a recommendation. The element of permission is indicative of the fact that it is at Israel’s discretion to grant return. Secondly, it is subject to two conditions: that the refugees wish to return and that they wish to live at peace with their neighbors.

In light of the present situation in the area, and especially following the violence that erupted in May 2021, it is questionable whether such peaceful coexistence can be ensured.

Since the wording of Paragraph 11 does not establish a basis for a “right of return,” the resolution, therefore, cannot be interpreted as establishing a legal basis for such a right. The U.N. General Assembly is solely entitled by the U.N. Charter to make recommendations that do not contain binding obligations, and it cannot establish legal rights. The resolutions, therefore, do not carry a force of law, and a “right of return” cannot arise from them. Therefore, Resolution 194 (III) must be regarded as nothing more than a recommendation concerning those refugees wishing to return and live in peace.

II. Security Council resolutions

A “right of return” does not appear in resolutions of the United Nations Security Council, the only organ that has the authority to adopt obligatory resolutions. The issue of Palestinian displaced persons was addressed by the UNSC following the 1967 “Six Days War” in Resolution 237 (June 4, 1967). The resolution called upon the government of Israel to “facilitate the return of those inhabitants (…) who have fled the areas since the outbreak of the hostilities.” The resolution, adopted under Chapter VI of the U.N. Charter, dealing with the pacific settlement of disputes, was not an obligatory resolution and made no reference to a “right” of the refugees to return.13

Furthermore, in its famous Resolution 242 (Nov. 22, 1967), which serves as the basis for the Middle East peace process, the Security Council solely “affirms further the necessity for achieving a just settlement of the refugee problem.”14 If a right of return had been previously established by Resolution 194 (III) of 1948, then it would surely have figured here as the basis for settling the refugee problem.

Lastly, a right of return does not appear in other international refugee situations. During the Kosovo refugee crisis, for example, in its Resolution 1244 (1999), the UNSC did not refer to a right of return.15 If the Security Council accepted a right of return, it would have applied it to the situation in Kosovo.

III. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

A right of return for Palestinian refugees can further not derive from international law sources dealing with human rights, such as the ICCPR. Article 12 (4) of this Covenant generally refers to a right to enter one’s country: “No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of the right to enter his own country.”

This Article is not applicable to the situation of Palestinian refugees. Firstly, it is questionable whether the term “to enter his own country” applies to Israel for Palestinian refugees. Secondly, it is disputed that the Palestinian refugees were arbitrarily deprived of entering Israel.

It is further advocated in international legal literature that the right of return in Article 12 (4) ICCPR is meant as an individual right.16 It was not intended to deal with claims of masses of people being displaced as a by-product of war and, therefore, cannot be applicable vis-à-vis the situation of Palestinian refugees.

IV. Israeli-Palestinian peace-process documentation

Lastly, the issue of Palestinian refugees is tackled by prior-ranking binding bilateral agreements between Israel and its neighbors.

Article A (3), subparagraph 5 of the 1978 “Framework for Peace in the Middle East between Israel and Egypt,” negotiated at Camp David, established a “continuing committee to decide by agreement on the modalities of admission of persons displaced from the West Bank and Gaza in 1967.” In subparagraph 6 of this agreement, Egypt and Israel agreed to “work with each other and with other interested parties to establish agreed procedures for a prompt, just, and permanent implementation of the resolution of the refugee problem.”17

Both the 1993 Israeli-Palestinian “Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements” (commonly known as “Oslo 1”), as well as the 1995 “Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip” (known as “Oslo 2”), referred to the issue of refugees as an issue to be negotiated in the permanent status negotiations.18

In Article 8 of the Treaty of Peace between Israel and Jordan (1994), the parties agreed to seek to establish a quadripartite committee together with Egypt and the Palestinians to deal with displaced persons, as well as a multilateral working group to deal with refugees.19

The 2003 International Quartet’s “performance-based road map to a permanent two-state solution to the Israeli Palestinian conflict” referred to the convening of an international conference to deal, inter alia, with the “revival of multilateral engagement on issues including regional water resources, environment, economic development, refugees, and arms control issues. “It also foresaw the final and comprehensive permanent status agreement ending the Israel-Palestinian conflict, with an agreement that would include “an agreed, just, fair and realistic solution to the refugee issue. “20

In summary, a “right of return” does not appear in resolutions of the U.N. Security Council, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) or in Israeli-Palestinian peace-process documentation.

* * *

Notes

1 UN General Assembly document A/C.4/76/L.12 dated 1 November 2021 https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/gaspd743.doc.htm

2 Meeting record A/C.4/54/SR. 17 para. 39, available here: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/419673?ln=en

3 Meeting record A/C.4/58/SR.17 para. 46, available here: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/539233?ln=en

4 Meeting record A/C.4/74/SR.25 para. 8, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N19/368/36/PDF/N1936836.pdf?OpenElement

5 See e.g. https://www.foxnews.com/politics/biden-reverses-trump-stance-on-palestinians-right-to-return-to-israel and https://www.jpost.com/international/us-changes-its-un-vote-from-no-to-abstention-on-unrwa-affirmation-684542 and https://www.palestinechronicle.com/us-changes-votefrom-no-to-abstention-on-un-resolution-on-palestinian-right-of-return/

6 https://www.unrwa.org/content/resolution-302#:~:text=UNRWA{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20is{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20created{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20by{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20General,conditions{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20of{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20peace{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20and{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20stability{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}E2{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}80{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}9D.

7 https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/statusofrefugees.aspx

8 https://www.unrwa.org/palestine-refugees

9 https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/043/65/PDF/NR004365.pdf

10 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Nations_General_Assembly_Resolution_194#Voting_Results

11 France, Turkey, and the United States were named as members of the Conciliation Commission

12 Ruth Lapidoth, “Do Palestinian Refugees Have a Right to Return to Israel?”, 2001, https://www.mfa.gov.il/mfa/foreignpolicy/peace/guide/pages/do{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20palestinian{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20refugees{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20have{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20a{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20right{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20to{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20return{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20to.aspx

13 https://unispal.un.org/DPA/DPR/unispal.nsf/0/E02B4F9D23B2EFF3852560C3005CB95A

14 https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/240/94/PDF/NR024094.pdf?OpenElement

15 https://unmik.unmissions.org/united-nations-resolution-1244

16 See e.g. Stig Jagerskiold, „The Freedom of Movement”, in Louis Henkin, ed., The International Bill of Rights, New York, 1981, p. 180, or Ruth Lapidoth, “Do Palestinian Refugees Have a Right to Return to Israel?”, 2001, https://www.mfa.gov.il/mfa/foreignpolicy/peace/guide/pages/do{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20palestinian{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20refugees{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20have{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20a{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20right{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20to{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20return{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20to.aspx

17 https://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/ForeignPolicy/Peace/Guide/Pages/Camp{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20David{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20Accords.aspx (Camp David Accords)

18 https://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/ForeignPolicy/Peace/Guide/Pages/Declaration{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20of{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20Principles.aspx, and https://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/ForeignPolicy/Peace/Guide/Pages/THE{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20INTERIM{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20AGREEMENT.aspx

19 https://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/ForeignPolicy/Peace/Guide/Pages/Israel-Jordan{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20Peace{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20Treaty.aspx

20 https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/IL{e421c4d081ed1e1efd2d9b9e397159b409f6f1af1639f2363bfecd2822ec732a}20PS_030430_PerformanceBasedRoadmapTwo-StateSolution.pdf

Amb. Alan Baker is director of the Institute for Contemporary Affairs at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs and the head of the Global Law Forum. He participated in the negotiation and drafting of the Oslo Accords with the Palestinians, as well as agreements and peace treaties with Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon. He served as legal adviser and deputy director-general of Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and as Israel’s ambassador to Canada.

Lea Bilke is a law student at the Free University of Berlin in Germany, specializing in international and European law.

This article was first published by the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs.